EXHIBIT

CREATING HOME

BLACK INCLUSION AND COMMUNITY BUILDING

In this exhibit you can explore the different phases of Solitude’s history. We begin during the period when this place was indigenous land, and go on to explore its history as a slave plantation in the nineteenth century.

Despite Virginia Tech being the first historically white institute of higher education in the former confederacy to admit black undergraduate students, their arrival could not erase the history of racism and discrimination that are integral to the history of Virginia Tech. For when black students arrived on campus, they were met with both symbols of hate, and while many white students went out of their way to promote diversity and inclusion on campus, others fought to limit it.

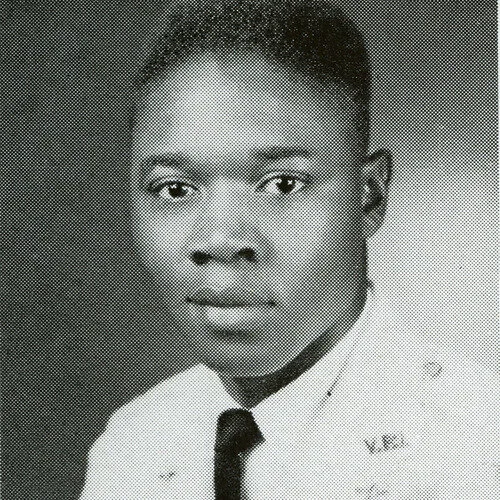

Until 1970, the playing of Dixie was accompanied by the proud flying of the Confederate Flag at all Virginia Tech sporting events. Although the song and flag were interpreted as symbols of white supremacy by black and many white students, a large majority of the student body felt that these were merely symbols of Virginia Tech’s honored history, and that those that did not approve were welcome to go to school elsewhere. Marguerite Harper Scott, who worked to remove the Confederate Flag and playing of Dixie from her role on the Student Senate, recalls her experience with the flag and playing of “Dixie”: "College Characters" from 1899 Bugle, depicting several Black workers of VPI including Floyd "Hardtimes" Meade Irving Peddrew III in cadet uniform, 1953

“When they played "Dixie," it was expected that people would stand, as if it were the national anthem. I recall at a game I said, there's no way I'm standing for "Dixie." And I remember someone punching me in the back at a football game and saying something to the effect about how I should stand...The interesting thing about that is that they would take the Confederate flag down when an important African-American came to visit, such as an Erroll Garner....So then you said, okay, well obviously they felt that this would be insulting to him. Why don't they think it's insulting to me, and I'm paying university fees and what have you…” The Class of 1973 was the first to have the option not to have the Confederate Flag on their class ring. Students had the option to pick either the Confederate or United Nations Flag. When the SGA proposed a resolution that would remove the Confederate Flag from Cassell Coliseum, many white students protested by flying their own Confederate Flags out of their dorm windows while loudly playing “Dixie”. By 1971, it was clear that both the flag and song were detrimental to recruiting top athletes, and the athletic program successfully lobbied for the removal of both. Again however, white students were not ready to let go of tradition. James Darnell Watkins (‘71) recalls when white students brought their own flags to fly after the Confederate Flag was taken down from Cassell: “When they decided to take the Confederate flag down, every student there, almost every white student came in with their own little Confederate flag at the basketball game. I'll never forget it. Here we were happy that the flag was going out of the Coliseum, but every student had a little flag. Their protest was ‘you can take our flag down, and we're going to bring our own flag’....You wanted to feel comfortable with your surroundings. "Dixie" and the Confederate flag didn't help that.”

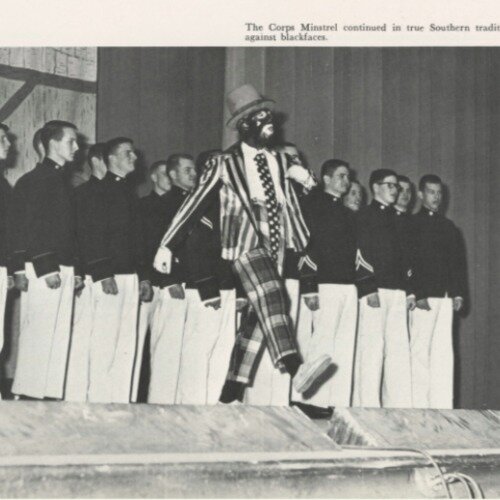

In addition to these celebrations of the Confederacy, Virginia Tech’s Corps of Cadets also had a long history of minstrel show performances dating back to performances by the Virginia Tech Minstrels in the early 1900s, and lasting well into the 1960s. At the Corps' 1964 minstrel performance in Burruss Hall, a group of students protested the performance, as they believed the celebration of racism brought shame and dishonor to Virginia Tech. The fact that many students defended the show and claimed that its depictions of blacks were not racist, but rather exaggerated stereotypes based in truth, once again showed how split the student body was in terms of inclusion for their fellow black students.

Member of the Virginia Tech Minstrels appearing in blackface, 1924 Bugle Corps Minstrel "end men", 1922 The Corps Minstrel's 1964 Performance in Burruss Hall. The photo's caption from the 1965 Bugle reads, "The Corps Minstrel continued in true Southern Tradition despite protests against blackface" 1964 Corps Minstrel's performance. The caption from the 1965 Bugle reads, "The end men give minstrel its traditional slapstick comedy" Although the above mentioned traditions were discontinued by the 1970s, student racism was still alive on campus decades later. In the 1990s, a mass email containing racially charged and discriminatory rhetoric was sent to the student body. The email was written in Ebonics, a controversial term used to describe the dialect of black Americans, and asked readers to respond to a series of questions alluding to racist stereotypes such as “check here, if you know something about food stamps.”

President Torgersen responded to this email and other instances of racism on campus with a strong statement condemning the actions in the Spring 1998 edition of Diversity News: In the early 2000s, the door of the NAACP office in Squires Hall was vandalized, with someone smearing the n-word across it. Around the same time, controversy over a fraternity dressing in blackface also erupted. Levi Daniels (‘05) recalls being asked by a white student what the problem with blackface was: "So Amy is like, 'Well what’s the big deal? It was just a costume.' And what I tried to explain to Amy was I was like, ‘Well let’s take a look at it this way, when you typically think of Halloween what are the things that you think of?' and she didn’t quite understand where I was going. And I was like, 'Okay, so you think of ghosts, ghouls, goblins, witches. What do all of those things have in common?' She was like, 'They don’t really exist.' So you’ve effectively lumped me into the same place with things that you don’t really think exist. I exist. I’m right here...But when you lump me in these groups that is marginalization without using the term. You’ve lumped me in the same group with things that you say don’t really exist. You are taking a moment to kind of don a persona that isn’t you, but it is me. It’s not a caricature, it’s not an idea, it’s me. I’m not an idea. I’m here."

List of Virginia Tech's first eight black students

In 2009, alumni and former Assistant Director for the Culture and Community Centers at Virginia Tech, Joe Frazier, faced racism on one of his first days on campus as an undergraduate: "I don't know if it's called the Summer Bash or what it is, and it's a big event in McComas Hall, like a big party that welcomes all the students...So we're waiting in line to go inside this event and so while we're waiting this group of basically it was white girls came out the building, and so I decided let me ask them how is the party on the inside, because if it's not worth it then we can go do something else, go find food somewhere else, whatever. So they were walking by and I walk up to them and I ask them, 'Hey, how's the party on the inside?' And they looked at me and my group and friends and said, 'Oh, well they have fried chicken on the inside so you guys will be happy.' So you know, I heard it. My group heard it. They got angry, but you know, they all walked off and it was one of those things like well, is this what Virginia Tech is going to be like being here, and that was the second day I guess at VT.”

Of course, these stories are only a few of the many such instances of racism faced by black students on campus. While Virginia Tech may have progressed past the need for debates over minstrel shows and Confederate Flags on campus, black students were continually discriminated against by their peers, even as the administration made considerable efforts to promote diversity and inclusion.

BLACK COMMUNITY ENGAGEMENT IN THE 1960S AND BEYOND BARRIERS OF ENTRY INTO WHITE CAMPUS CULTURE FORGING A STUDENT COMMUNITY A CONSTANT BATTLE BETWEEN INCLUSION AND EXCLUSION ADMINISTRATION PROMOTING DIVERSITY