EXHIBIT

WOMEN OF COLOR

PROFILES IN ACHIEVEMENT

CONFRONTING RACISM AND MAKING COMMUNITY ON CAMPUS

Being a BIWOC during much of the twentieth century in Blacksburg, Virginia could be especially isolating. This was a time when many of their white classmates believed that nonwhite populations were inherently inferior and actively supported white supremacy. This culture existed at Virginia Tech and was ingrained into its history as an institution.

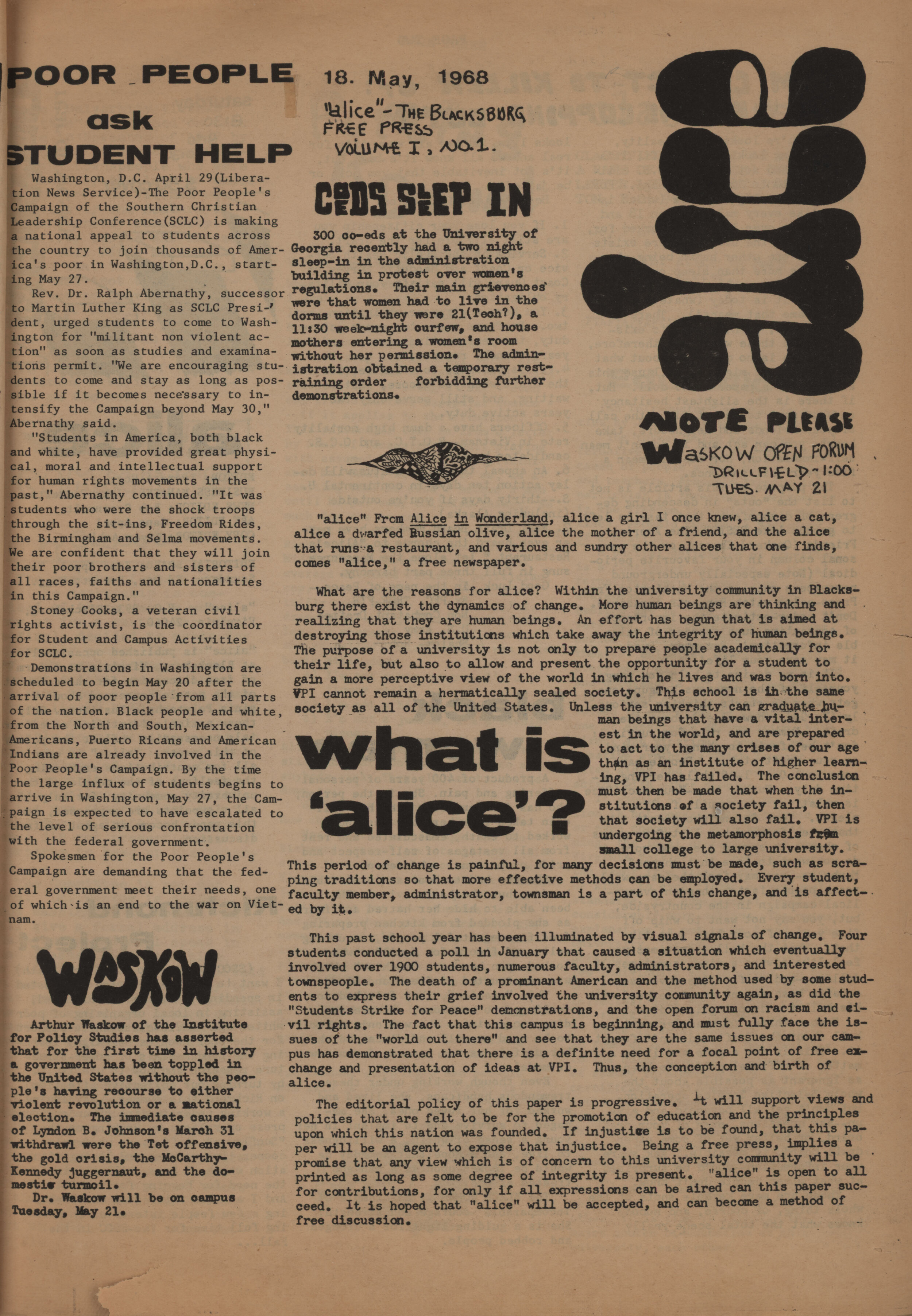

Screenshot from The Bugle 1968 - Cotillion Club

Black women dealt with Tech's student "traditions" head-on. Marguerite Harper (one of the first Black women to attend VT) recalls how she saw hatred expressed towards the Black community at football games: “The cheerleaders would come out on the field first with this huge rebel flag, and then the Highty Tighties would come out playing ‘Dixie.’ When they played ‘Dixie,’ it was expected that people would stand, as if it were the national anthem.” While the song, Dixie is offensive, Harper describes how the Black students were harassed if they silently protested by sitting through the song, “I recall at a game I said, ‘There’s no way I’m standing for ‘Dixie. And I Remember someone punching me in the back at a football game and saying something to the effect about how I should stand. I looked at that person, and I said, ‘You best not put your hands on me again.’” While some white students directly threatened student protesters, there were also many indirect acts of aggression that displayed the opposition towards the Black community. Harper and other Black students received hate mail and demeaning telephone calls in response to their activism.

On an often inhospitable campus, Black-centered organizations and physical spaces ensure a safe environment that promotes physical, mental, and spiritual well-being for students of color.

This was the only place that the African American community could gather publicly, other than in segregated churches, until integration in the 1960s and 1970s. Since neighborhoods were still strictly separated by race, the Black community didn’t get to enjoy the many amenities that their white counterparts did. The building allowed them to enjoy recreational activities, weddings, dinners, Easter egg hunts, and many more that would serve as a safe space for Black women to grow and flourish.

The Cosmopolitan Club reflected a sentiment among the broader white population across the United States: women of color were acceptable if they were from another country, or if they weren't Black. VPI was more willing to accept women of color that were "foreign" because of their lighter skin tone and because they weren't stigmatized by association with the formerly enslaved Black population.

VPI was cautiously wading into a more tolerant future, trusting and accepting that international students and students of color were acceptable. Women of color (like Yvonne Rohran Tung) flourished because of the Cosmopolitan Club, and left the door open for other BIWOC to follow.