EXHIBIT

THE LAND GRANT SYSTEM

BLACK INCLUSION AND COMMUNITY BUILDING

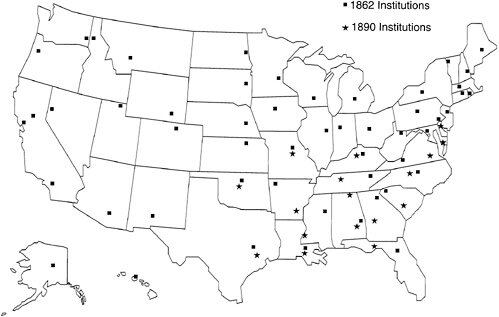

EXPANSION OF THE LAND-GRANT SYSTEM

For VPI, the 20th century saw continued expansion and growth. In 1921, the first women were admitted and in 1953, the first African American. Although the school remained primarily focused on military instruction partnered with agricultural and mechanical curriculum, by the 1960s the school began offering degrees in English, History, and Political Science. By the end of the decade, the school was operating as a full fledged university, and in 1970, the Virginia General Assembly bestowed University status on VPI, giving it it’s formal name today, Virginia Polytechnic Institute and State University.