EXHIBIT

THE LAND GRANT SYSTEM

BLACK INCLUSION AND COMMUNITY BUILDING

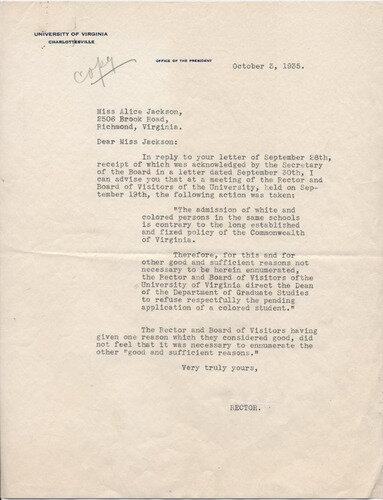

HIGHER EDUCATION FOR AFRICAN AMERICANS IN VIRGINIA

In 1946, Virginia State College for Negroes dropped the end of its name and became Virginia State College. Today, it is Virginia State University. Although open to all races, today VA State’s racial makeup is almost 94% Black. Virginia’s largest land grant school, Virginia Tech first opened to only white students, and today less than 5% of students are African American. Although legal segregation ended in the mid 20th century, the landscape of higher education in Virginia remains separated by race.