EXHIBIT

THE LAND GRANT SYSTEM

BLACK INCLUSION AND COMMUNITY BUILDING

VIRGINIA TECH AND INDIGENOUS LAND

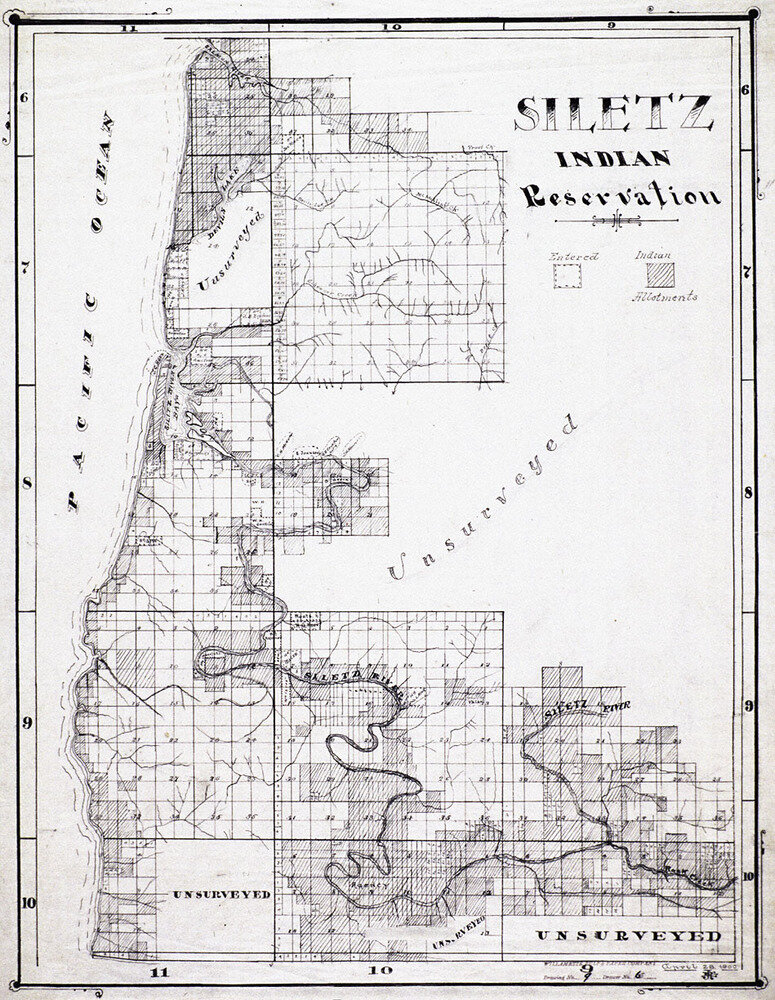

By 1954, the federal government began the process of terminating groups within the Confederated Tribes of the Grand Ronde Indian Reservation and by 1956 over 60 tribes in Western Oregon and the surrounding area had been terminated. This process of termination forced many to relocate and look for employment in cities, contributing to the reduction in indegenous culture. In 1983 however, the Grand Ronde Restoration Act was passed, restoring 9,811 acres of the reservation's original land. Since, the Confederated Tribes of the Grand Ronde Community of Oregon population has reached over 5,000 and they are actively engaged in collaborative projects with state and local agencies, helping to educate the public on their indigenous history.

This is just one example of the hundreds of broken treaties and violence backed land cessions used by the US federal government to acquire tens of millions of land in western territories. Without this land, the Morrill Act of 1862 would not have been possible, and the land-grant system as we know it may never have come to fruition. Today, many universities are working to repay their debt to indigenous communities in a variety of ways.